Because of what I do and where I live, I am often talking with people about the human-wildlife conflict, and am continually surprised by what I hear. There are many misconceptions about our relationship with nature in general and with wildlife in particular. During these discussions, I notice there are several persistent themes (false beliefs) that are pervasive about the human-bear relationship. What I hope to do over the course of several posts is to examine these key themes and shed light on these common false beliefs. Other posts in this series are, ‘How to make bears and fruit trees get along‘ and ‘Bears and fruit trees, part three.’

As ever, I welcome your feedback and comments as they can add to the discussion and help me develop my position.

False belief #2: We are not in competition with bears

Many people don’t understand that, despite trappings of modern civilization that buffer us from this reality, we are in direct competition with wildlife for our existence. Not only have we lost sight of this fact, but we have also begun to believe that there is a way to ‘live in harmony’ with nature and we work hard to convince ourselves this is achievable.

If you are one of these people, then you are wrong to think this way and here’s why.

Everything out there is trying to make a living just as we are, from the bears, to the fish, to the squirrels, to insects, and bacteria. Since humans have walked on this earth we have been in direct competition with nature for resources and thus have fought to protect these resources. If we weren’t successful, we starved.

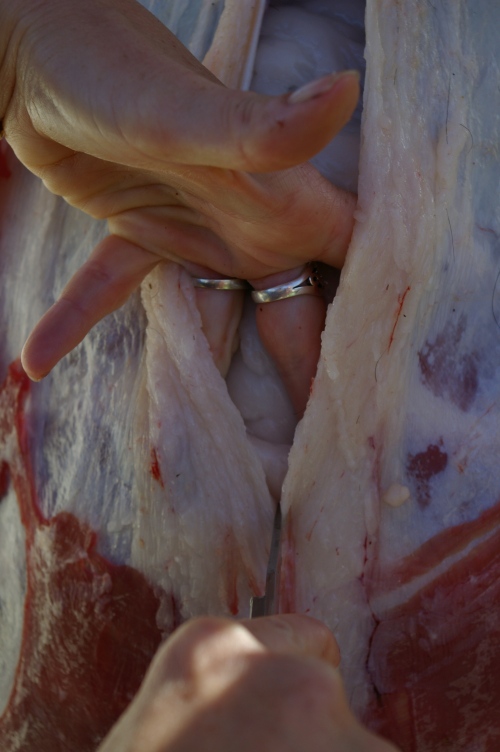

Historically, humans hunted for our food and thus we understood our direct relationship with the natural world. We understood that if the wolf population was too high the deer numbers would be low and this would threaten our chance of survival. Consequently, humans understood we needed to kill some wolves in order to protect the deer numbers and, in this way, indirectly protect our own species‘ survival. We understood we were, and must be, part of that equation.

Today, every time we spray our lawns with insecticide, every time we build a new home, each time we pave a road, each time we build a shopping mall or a university, each time we fell trees to make lumber, every time we fill our gas tank, every time we buy some product that has been shipped half way around the world, every time we buy packaged food from the grocery store, and so on, we displace and destroy (or already have replaced and destroyed) the native plants, insects, birds and animals — and the resources they depend upon for their survival — that previously existed in the are area in question for our benefit.

Today however, few people would recognize the environmental cost to changing a track of forest into agricultural land and the inputs necessary to raise a cow, or a pig, or even an acre of soybeans to grow food for humans. Few would understand that it is environmentally more sound to keep the forest in tact and harvest a moose who is perfectly suited to that forest and requires no artificial inputs, let alone be willing or able to make the lifestyle changes necessary to manage that resource.

Only those who can afford food can ‘afford’ to entertain this false belief system.

Few people in North America today rely on hunting or raising food on their own land for their direct economic survival. Instead, we have accepted that large swaths of nature should be severely altered (if not completely destroyed) in order that we can live in city suburbs, and that agricultural (and other) products can be made cheaply and can be transported long distances to us. So it is not that we are no longer directly in competition with nature, rather that the competition is out of sight and out of mind. We are no longer aware of it because we don’t see direct evidence of it on a daily basis.

California’s bears and other flora and fauna have been displaced and/or all but been destroyed, its landscape severely altered to make way for suburbs, highways, orchards and market gardening, and its waterways re-routed for irrigation, as have the Okanagan and Frazer Valleys in British Columbia, great swaths of the prairie provinces across Canada and the USA, and the Niagara region of Southern Ontario. These areas are some of the major agricultural production areas on which we North Americans depend most for our food production and, therefore, survival. That these areas were once wild, and remain domesticated only by force and vigilance, is an idea forgotten or ignored only by those who can afford to buy food instead of growing it themselves (provisioning). It is only those whose economic livelihood is not threatened, those who live an indirect economic lifestyle by selling their time for a wage so they can buy food, clothing, housing, etc., for their (indirect) survival, who can afford to uphold the misconception that we are not in direct competition with wildlife for our existence.

We all are in competition with nature, even urban dwellers. Ironically, it is urban dwellers who are, not only the most food insecure because they are more dependent upon an agricultural production and distribution system that is completely out of their control, but also often the most unaware of how much competition they are in with nature for their survival. How many urbanites consider the tons of pesticides that are sprayed annually on wheat alone to keep the average crop from succumbing to weevils? While weevils are not bears, they too compete directly with us for our wheat!

Which brings me to two other important points about direct competition.

The privilege of living close to nature

We have developed strategies for competing with all aspects of nature, from traps (mice and rodents), to fungicides, herbicides, insecticides (molds, weeds, bugs), to windbreaks and rip-raps (erosion by wind and water). We have become so conditioned to these agricultural weapons that we no longer see them as such. We certainly don’t see weevils on par with squirrels, or squirrels on par with grizzly bears. Many bear enthusiasts would not object to a farmer spraying crops to prevent weevils from destroying it but would be horrified if the same farmer shot a bear to protect his apples. However, if you were dependent upon the apple crop for your livelihood, or to keep you from starving, you wouldn’t. The privilege of a full stomach affords us the luxury of seeing these two actions as vastly different. Today, most North Americans would tell me to go buy the apples from the store and save the bear because they are no longer engaged in direct economics and can afford to be blindly unaware of the cold hard realities of what it takes to put food on their tables.

If you have a stomach full of food bought from the grocery store, then you can afford to see squirrels, deer, hawks, and bears as part of the wonders of nature and feel ‘privileged’ that they are traipsing through your yard and let them eat your berries, apples, and carrots. But even then, there is a big difference between tolerating squirrels, deer, and hawks, and tolerating bears and other large predators. Squirrels can’t kill you but large predators can. In order to keep our yards and communities safe, we cannot tolerate large predators in our human settlements, period.

However, if you are dependent upon the food you raise for your economic survival (directly or indirectly) you cannot even afford to let the squirrels eat your strawberries or the deer eat your apples. Imagine that every time a deer came in to your yard you lost 1/3 of your annual wage. How long would it take before the joy of seeing a deer to wear off? How long could you ‘afford’ to feel privileged at losing 1/3 (or more) of your annual salary? In order to have food security, you must have the right to defend the food.

In Defense of Food

In short, humans have a right to livelihood. By that I mean the right to grow food instead of selling our time, collecting a wage, and then spending it at ‘the store’ (where cheap food magically appears). We therefore have the right to defend our food sources just as we did in the past. Salaried employees don’t lose wages when a bear comes through their yards, why should a provisioner or farmer? Some will argue that that should be part of the cost of ‘doing business’ as a farmer. Many will argue that I (and other farmers) should buy electric fencing, install bear proof feed bins, build bigger, stronger, bear proof chicken houses and so on in order to prevent the bear conflict. I am against this line of thinking for three reasons: this argument is based on false belief #1 (that humans can control bear behaviour by removing all attractants); there is little enough (if any) profit to be made in farming these days and the additional cost would make their products out of reach for many consumers; and finally, fencing out large predators and leaving them to roam the neighbourhoods around fence lines does not promote human safety.

If we want sustainable farming to be something that younger people choose as a career, if we want food security for our communities, if we want to have agricultural animals raised ethically and humanely, if we want good clean safe food, if we want the right to livelihood, then we have to support those who are willing to do the work and make it worth their while. Otherwise, we will have to accept that those farmers who could get well paying, secure jobs elsewhere, should get them; that we will have food insecurity; that we will give up our right to livelihood; and that we will have to rely upon the corporate agricultural production and distribution system.

Finally, because we all need to eat and that act displaces large tracks of wilderness in order to ensure our survival, then the cost of maintaining wilderness with its full compliment of flora and fauna, in parallel with local food security, should be borne by all society, not just those who choose to live close to the wild and raise our food.