As many of you know, I’ve not been at Howling Duck Ranch for several months now. Living away from my home, the ranch, and all my animals has not been easy. Consequently, I’ve been remiss with my regular posts. I have struggled with many things these past few months: from the lack of anything to write about (what do I have to say without my farm?), to the lack of desire to bore you with my life’s struggles. After all, that is not what brought you to this blog!

Suffice it to say, these past few months has been full of difficult decisions: downsizing the ranch, possibility selling the place, and finally, dissolving my marriage.

Thankfully, I’ve had a friend living at Howling Duck Ranch. She’s been doing a wonderful job of taking care of the place and the animals, which has been a huge relief for me. She has, quite literally, helped keep the wolves at bay! However, she can only stay until June and I’ve not yet found a suitable or affordable alternative for the Howling Duck Ranch crew. Consequently, I’m faced with being realistic and that means disposing of some critters.

My farm sitter friend is helping with this task and has already given away many of my chickens. The goats however are not easy to find homes for. Moreover, I’m emotionally attached to them. I can’t quite part with them yet–they are my family.

However, I couldn’t avoid the facts forever. A couple of weeks ago, I had some time to get away so I planned a quick trip into the Valley to butcher some of the kids. Even a few less goats to feed at this stage would be helpful. I know this sounds contradictory to their status as family, but the boy kids always were destined to be food. Also, I convinced myself that rather than give them away and risk them being eaten by a grizzly bear or cougar, I’d end their lives myself–at least I know it will be done quickly.

While planning my trip, a blog follower sent an email requesting to visit Howling Duck Ranch and wondered did I do ‘farm stays’. Before leaving the ranch in January, I was planning to do just that. At the time, I wasn’t sure how to make that happen or what it would look like. Suddenly, before my eyes was an email request that had nestled in it an offer I couldn’t refuse: “If you ever need help with butchering goats, I’d be happy to help out.”

We exchanged a few more emails (one of which he confessed to having run a butcher shop!), and before I knew it I was planning my first ‘hands on farm stay’ experience at Howling Duck Ranch! Not only that, with someone who had a skilled set of hands. What I didn’t know at the time was just how many hands would be at my disposal that weekend.

The morning started out as planned, with me rounding up the kids:

Making the killing shot:

Prepping the carcass by hanging it in a tree, ready for skinning:

However, it wasn’t long before the men were involved. Before I left Smithers, I called Clarence to say I’d be in the valley (I’d never hear the end of it if he found out I’d been in town and not visited), and my friend Mike Wigle to see if he was interested in taking some photos (I encourage him to develop a farm photo portfolio every chance I get)! Both men agreed to come to the butchering day. But it was my farm stay visitor who was ‘first man in’.

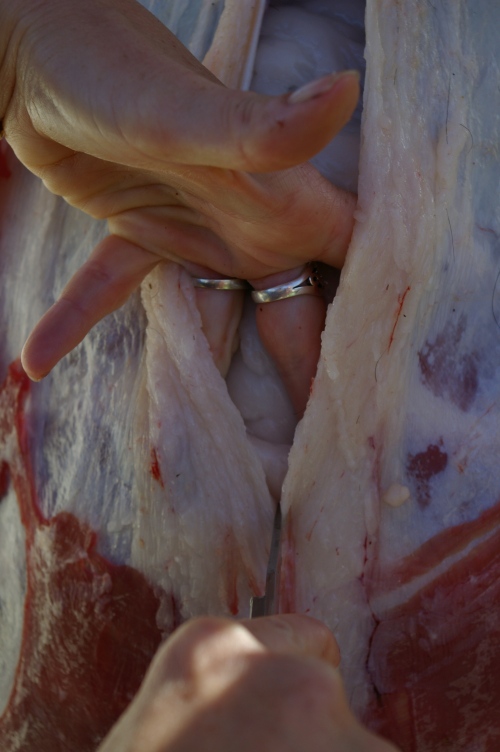

Enter stage left. Jeff jumps in to help with the skinning process:

Jeff is the first man in on the scene and is laughing at how small and easy a goat is to butcher compared to the huge cattle beasts he's accustomed to working with.

Jordan came with Clarence and is soon eager to get his hands in on the process too:

There were some comments about the lack of edges on my knives followed by a request that I find a wet stone. As I dashed off in search of the stone, the men quietly moved in and without ceremony, took over the job:

The three of them made light work of the butchering process and I was thrilled to have the help. It gave me some time to visit with my friend Colleen, who I’d not seen for months and had dropped in unannounced for a visit. Without the men at work, stopping to visit with Colleen was a luxury I would not have otherwise afforded:

Eventually, even the dogs got in on the action:

Colleen’s tiny pooch ‘Peanut’ gives a first rate effort as part of the ‘clean up’ crew:

It is not long before the goat is in pieces:

Clarence and Jeff take over the process and cut the goat into recognizeable cuts of meat. Note: I love the look in Tui's eyes. She knows she's in for a treat as does the chicken!

Soon we’re ready for round two. At this stage, I barely have to lift a finger, let alone a goat:

Although a fast and furious paced weekend, it was a wonderful visit home. Thanks to the men who stare at goats–my new friend Jeff, and my wonderful old stand-by’s Clarence, Jordan, and Mike–it was made all the more enjoyable. Thanks guys!